Triggering a Crisis in the Wycombe Chair Industry

Researching the census returns for nineteenth-century Downley is a frustrating affair. Nothing comes up if one just enters ‘Downley’. We were ‘West Wycombe Enumeration District 10’ (or 16 or 5d, depending on the year) encompassing ‘Downley, Littleworth, Plomer Green, Plomer Hill& Henley Pitch’ from 1861. The challenges mount up: the 1871 census is almost illegible and has spelling errors; the 1881 one is faint; only a handful of houses are ever named (one in 1841, and five by 1891); and the first time a street is mentioned is 1891, and even then Chapel Street’s houses aren’t numbered. (It does make one wonder: Did no one get letters? Tax demands? Were exact addresses irrelevant? Did the postman just know where everyone lived?)

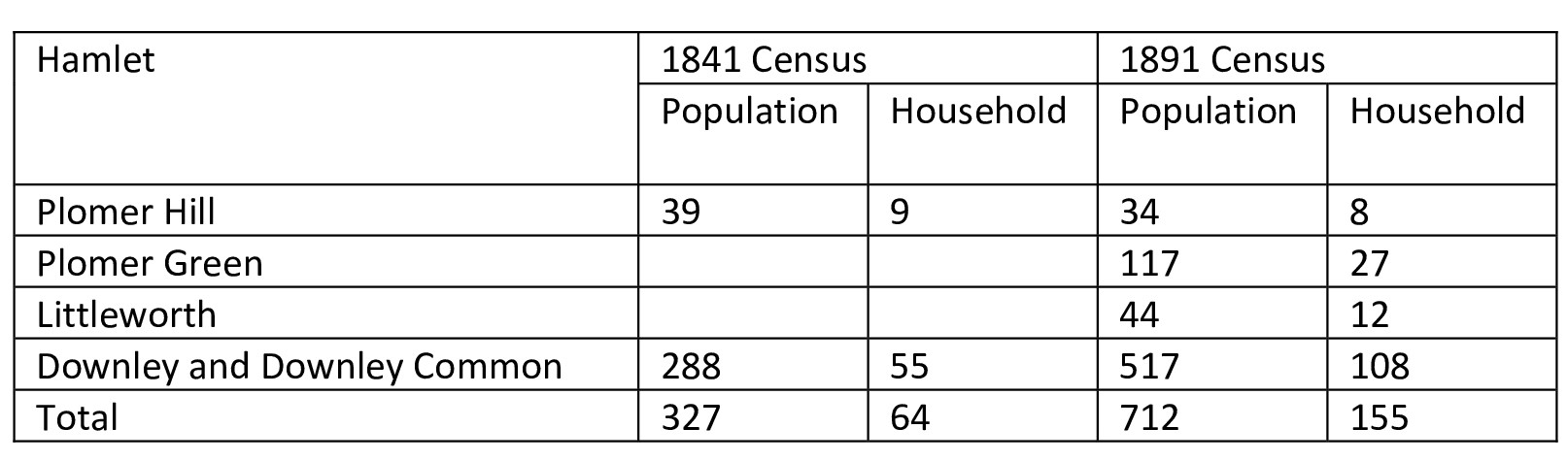

Stick with it and some fascinating things emerge. Apart from Plomer Hill, which didn’t change much, District 10 was booming. In the fifty years after 1841, its population more than doubled, boosted by a surge of incomers from surrounding Bucks villages and, in some cases, from much further afield – London, Reigate, Warwick, Birmingham, Nottingham, Carlisle and even, randomly, France. In fact, by 1891, only one in five of the adults living on Downley Common was born there. Littleworth and Plomer Green aren’t even mentioned in the 1841 or 1851 censuses; by 1861, they were distinct hamlets. In 1861, there were 21 houses on the Common; by 1891 there were 38.

So, what drew all these people? Job opportunities. Chairs, unquestionably. The most repeated word on the 1891 census is ‘chair’. (Fifty years earlier it was ‘Ag Lab’ – agricultural labourer – with ‘chair’ in second place.) Two thirds of all the District 10 adult males (defined as 11+, since 10 was the school leaving age) worked in the chair industry in some capacity or another. The majority – over 120 of them – were generic ‘chair makers’ or ‘apprentice chair makers’, but one also sees a few chair turners (‘bodgers’), chair bottomers (dangerous work!), chair framers, chair polishers, chair matters (a mystery), and chair packers. Many may well have made Windsor chairs (on which, see below) – Wycombe was famous for them.

And the other third of the 1891 male population? A few boys stayed on at school, three dozenmen worked on the farms, a dozen worked as general labourers, and three ran the pubs, and then it’s as though there was one of everything possible needed to make the District 10 community completely self-sufficient: a butcher, a baker, a grocer, a general storeman, a coal dealer, a dairyman, a shoe maker, a bricklayer, a stone mason, a sawyer, a wood carver, a cabinet maker, a blacksmith, a wheelwright, a carrier, a nagman, a mechanic, a gardener, a teacher, a lawyer, and even – how useful – a soldier (Sgt. Jesse Bristow, 3rd Oxford Light Infantry), and two plate layers (who laid railway tracks). To this one can add the work done by those District 10 women who earned livings as domestic servants, laundresses, dress and shirt makers, lace and bead makers, and rush mat makers. Women monopolised just one part of the Downley chair trade (but one you need to remember, for it brought Wycombe to its knees): twenty of them were the chair caners.

The self-sufficiency of the District 10 community would have been enhanced by the fact that in the 1880s most of the chair workers would have been able to work locally. At least three chair factories (if that is not too grand a term) may have operated up on the hill. The biggest of these was run by William Collins, who employed 56 people in 1881. He was 25 at the time and had inherited the business, established 30 years before by his grandfather, from his father Henry in 1877. Mary Collins (no relation) ran another factory which employed 27 men in 1881. Enos Bristow, Downley born-and-bred, employed 55 hands in 1881 when he was just 33, having established his business from scratch. The ability to work locally – to avoid the four or five-mile- round walk to High Wycombe or West Wycombe – unquestionably made life easier for men and women of District 10.

It all sounds very idyllic and compared to the 1850s, it probably was. The words ‘pauper’ stopped appearing on the District 10 census returns. However, the chair industry should not be romanticised. The Bucks Free Press called it a ‘system of slavery’. A six-day week operated, and many endured a 14-hour day, working from 6 am to 8 pm. Some of this work, like bottoming a chair seat using a hand-adze, was dangerous (which might explain the frequent use of the word ‘cripple’ on the 1851 census) and some hazardous. Workers risked the lung diseases associated with dust, while finished chairs were stained with a mixture that included nitric acid and urine.

However, the real source of grievance was low pay and impossible piece rate targets. Worse still, some employers used the illegal ‘truck system’, paying their employees part in cash and part in tokens, which could only be spent in expensive shops run by themselves or relatives.

To improve matters, Wycombe’s workers formed a Chairmakers’ Union in May 1872. Something like half the local chair work force joined this union including, almost certainly, the Downley caners. Matters came to head in July when Henry Collins of Downley, a local Wesleyan preacher, who had recently inherited W Collins & Son, locked out his caners.

Frustratingly, we don’t know why he did so, but the women’s cause was clearly felt to be a just one since the workers (possibly Downley folk?) at Benjamin North’s factory in West Wycombe and at Alfred Stone’s factory in Wycombe declared a strike in sympathy. In retaliation, the chair manufacturers of Wycombe collectively decided to lock out all union labour. Crisis ensued as the chair industry spiralled down into stagnation. This bitter dispute took months to resolve, and the vicar of Wycombe deserves credit for mediating the settlement (an end to the truck system and fixed and fair piece rates) that lasted to 1913.

On an end note, Methodism is sometimes hailed as a reason why England avoided a workers’ revolution in the nineteenth century, so there is a delicious irony in the fact that, here, an Anglican vicar resolved a crisis triggered by the actions of Downley’s Wesleyan preacher.