Chairs, Chapels and Children

“Chairs, Chapels and Children”, that is one description of the High Wycombe society in the 19th century, and indeed it could have been that of Downley itself, but it is necessary to go back some 500 years to understand the social and spiritual movements that led to the religious upsurge in Downley in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Religious dissent and non-conformity from the Catholic and Anglican Church had always been a major role in social evolution in the Chilterns. For example, in 1506 the ‘Lollards’, dissenters and freethinkers in Amersham, came to the attention of the Bishop of Lincoln and seven of them were burnt at the stake (the Amersham Martyrs). Then in 1532 Thomas Harding of Chesham was burnt. The news of these martyrdoms spread across the Chilterns and the ‘free thinkers’ had to go under cover. In 1665 six Quakers in North Bucks were sentenced to be transported. One centre of dissent was at Wooburn near High Wycombe, where Lord Wharton, one of the leaders of the ‘Puritan’ party in Charles II days, was a prominent dissenter. It is interesting to note that the Chiltern Hills closeness to London at times gave refuge to many ‘outcasts’ from society, the hills, woods and commons giving shelter to those who could not fit in with the cultural standards of the time.

Downley has always been influenced by the nearby town of High Wycombe, in the valley, a mere 40 minutes walk away. With the town’s market on three days a week, and as a supplier of work opportunities it is not possible to fairly treat Downley, the village on the hill, as an independent economic settlement though cultural and social life have given the village its own strong identity.

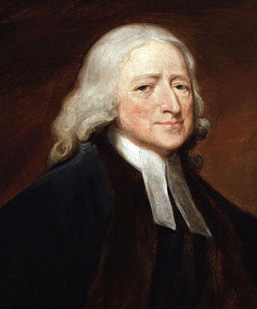

In the mid-18th century Downley was merely a collection of cottages scattered around hilltop common land, as hamlets at Littleworth, Plomers Green and Downley. Then came the beginnings of ‘organised’ free thinkers in the appearance of John Wesley, the founder of .Methodism*, when he first preached on 2 March, 1739 in High Wycombe. Wesley was a frequent traveller between London and Bristol, via Oxford, and he often stopped in High Wycombe to preach to the citizens of the town and the surrounding villages. The following is an extract from Wesley’s diary, 1746 – I came to Wycombe, it being the day on which the mayor was chosen – abundance of rabble, full of strong drink, came to the preaching on purpose to disturb, but they soon fell out amongst themselves, so as I finish my sermon in tolerable quiet. Wesley is recorded preaching in High Wycombe on a number of occasions spread over many years. It is of course highly probable that Downley people would walk down the hill into the town to experience the words of Wesley.

John Wesley did make progress with the town and villages around, in 1766 – I rode to Wycombe, the room was much crowded and yet could not contain the congregation, in the morning they flock together in such a manner as has not been seen before-and in 1770 – we had little prospect of doing good here but now the seed which has been so dead springs up into plentiful harvest.

Following Wesley’s visits, the beginnings of significant organised chapel and church life was growing, and particularly within ‘free thinking’ communities in the villages scattered around the Chiltern hilltops, and Downley had, in the early 19th century its own growing movement of dissent from The Anglican Church of England.

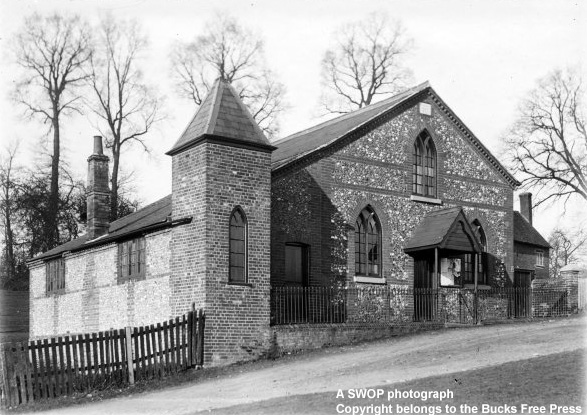

A James Treacher of West Wycombe started cottage services at Downley in 1818, and John Wright, a local Methodist preacher lent the money for the building of Sunnybank Chapel in 1824 (still active today in 2020, the oldest Chapel still in use in the Wycombe circuit). In 1850 Sunnybank Chapel was widened and enlarged and the building we now know emerged, with the addition of the schoolroom in 1924, to mark the first centenary. Will there be another in 2024….

During the turn of the 18th into the 19th century the ’Primitive’ Methodists arrived on the scene. The ‘Prims’ broke away from the more ordered, disciplined and dignified Wesleyan Church, they wanted a less formalised worship and less ministerial authority. The ‘Primitives’ organisation was expelled from the central Methodist authority in 1812. They preached in ‘camp’ meetings in the open air and ‘revival’ meetings spread across the land. In 1835, just 11 years after Sunnybank Chapel was built, a Reverend James Pole from Hounslow walked the 20 miles to High Wycombe and preached in Queens Square. He went on to preach in the hilltop villages and on Friday 10 of April I preached at Dounley (sic) in a wheelwright’s shop, and on 11 April visiting praying, Dounley is an obscure village, but it has a chair manufacturing which employs near 40 hands (this preaching was similar to the ‘evangelical’ movement we see today). In 14 April at Dounley at dinner time held a prayer meeting in the open air, they were more than 100 people, several wept, and some found peace with God. Tuesday 28, At Dounley in the open air, a large congregation, a mighty influence prevailed and the powerful conversion took place.

Reverend Pole continued his work. In 1864 the ‘Prims’ were organised enough to build their own Chapel in the centre of Downley, in what became Chapel Street.

The Chapel closed in 1965, for 101 years maintaining its separation from the Wesleyan Methodists across the Common at Sunnybank, even in the face of the Methodist Deed of Union in 1932, when the various alternative Methodist churches were combined into the one Methodist Church.

The Primitive Methodist Chapel is now a private residence, it keeps its characterful Chapel architecture. In 2020 Sunnybank continues its work within the Methodist movement, adding a great deal to the life of the Downley community.

*The term ‘Methodism’, or Methodist, originally described the members of the ‘Holy Club’ at Lincoln College, Oxford, John Wesley’s bible college. Their ordered habits earned them the nickname ‘Methodists’.

There are some fascinating records of the times in the book ‘250 Years of Chiltern Methodism, by BP Sutcliffe & DC Church, pub. Moorleys Bible & Bookshop Ltd from which the extracts above have been taken.