Downley Common, Its Origin and Survival

within the Manor of West Wycombe

This article is based on material presented by Dr Frances Kerner, Commons Re-registration Officer for the Open Spaces Scociety, at the February 2020 meeting of the Downley Local History Group.

Background

For those living in Downley, with its backdrop of green fields, woods, open spaces, and above all Downley Common, it is hard to imagine that but for a fortunate combination of events/circumstances the Common as we know it, could possibly today be the site of a large housing estate. To understand why this did not come to pass it is necessary to look at the history of Downley Common, but we must first explore what is meant by common land and by a manor.

Common Land is defined as land owned by another over which other people have the right to access and to take away natural resources for their own use. These resources can include pasture, pannage (the right to feed pigs or other animals in the woods), and estovers (the right to collect wood) amongst others, with the restriction that the resources cannot be sold to another. These rights are known as ‘common rights’ and are generally, but not exclusively, attached to a property.

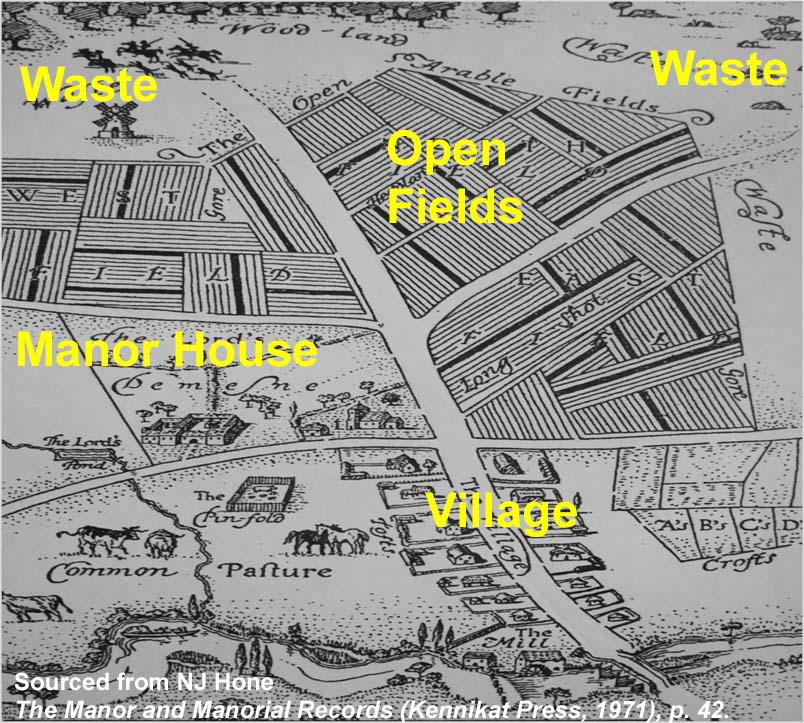

A manor is a single administrative unit of a landed estate, and can cover the same area as a parish (as in the case of West Wycombe). The figure below shows a schematic diagram of a thirteenth-century manor.

In the centre of the diagram is the manor house, nearby the church, and three large, open fields. The open fields are farmed by people from the village in a co-operative system of agriculture. For example, wheat is grown in one field, barley/oats in another and the third is left fallow. Each year the crops are rotated. Around the edges of the estate are areas of what was then known as ‘waste’ which had the status of common land. This is land where typically the soil is poor, crops cannot be grown and from which the Lord of the Manor cannot make a profit. In this system of agriculture, animals are of great importance particularly in ploughing and transport of goods but they need to be kept off the growing crops. Thus, they are usually pastured on the waste areas, provided that their owners had common rights. It is this land that survives today as common land.

Downley Common and West Wycombe Manor

The Manor of West Wycombe, which is referred to in the Domesday book of 1086, covered over 6,000 acres, stretching approximately from Downley in the east and Studley Green in the west, to Bradenham in the north and Booker in the south. Commons, i.e. areas of waste in the Manor of West Wycombe, included Downley, Naphill, Booker, Lane End and Wheeler End. Early records of the manor include references to Downley where it appears that people were encroaching on land that did not belong to them. For example, in 1245 Gervase de Dunle was fined ‘½d for pasture, 18d for 1 rood, rent 3½d so that he might not be heyward. 12d for an offence of pupresture. 12d for sheep being impounded (ref 1). ‘Pupresture’ signifies encroachment. We cannot know for certain where Gervase de Dunle was encroaching, but it may well have been on the Common at Downley.

(ref 1): With thanks to Simon Neal for supplying this extract. Hampshire Archives and Local Studies Ref: Pipe Roll no.18, 11M59/81/18

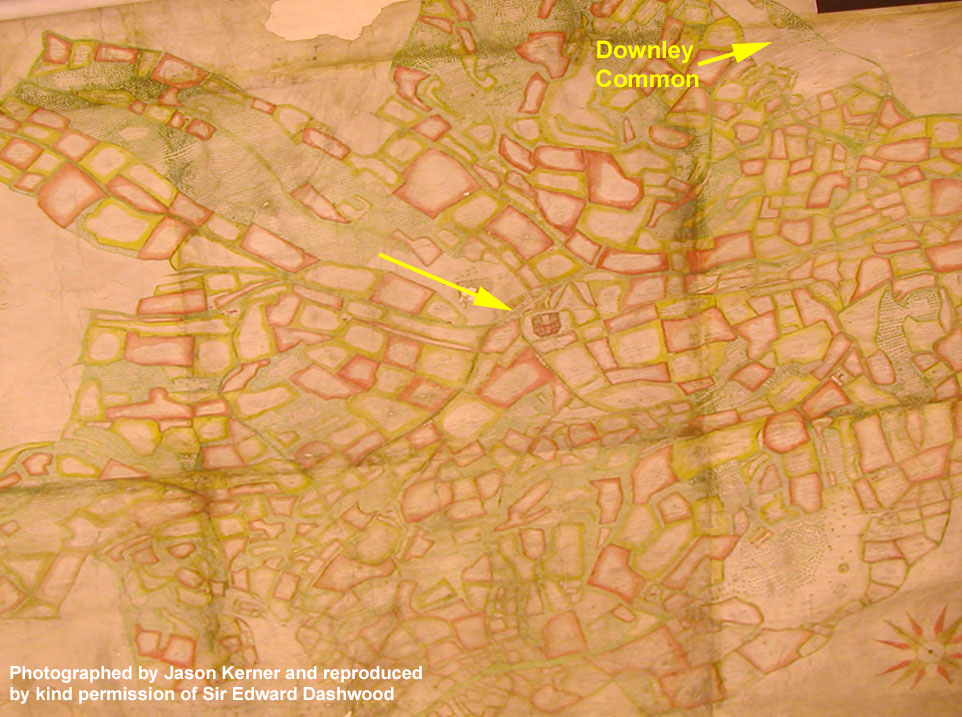

An order issued by the manor court in 1693 records that Thomas Russell and Ralph Roll shall make or cause to be made a good and substantial gate to be made at Henly Pitch at Plomer end Green to keep cattle upon Downley Common….. Henly Pitch at Plomer End Green Downley Common (the same place having time out of mind had a gate there which hath been maintained at the charges of the said Thomas Russell and Ralph Roll or those under whom they clayme their respective estates). The purpose of the gate was to control access of animals to the Common but we don’t know when this gate was first erected. However, when we look at the early 18th century map of the manor, the shape of the fields immediately to the north of the gate suggests that formerly, the Common extended to Plomer Green.

In the 1696 valuation of West Wycombe Manor, which was probably associated with its sale, Downley Common was recorded as having 120 trees, the majority being beech, whilst Booker Common had 2745 – again with the majority beech. Similarly, records show that the volume of poles (the straight stems of a slender tree stripped of its branches) and faggots (bundles of sticks, twigs or brushwood tied together for use as fuel) collected from Booker Common in the early 1820s was around 50 times greater than that collected from Downley. This highlights the pastoral importance of Downley Common, and although tree coverage of the Common has increased over the past 100 years a large proportion is still grassland.

The very early 18th century map of the Manor of West Wycombe shows West Wycombe House disproportionately large in comparison to the rest of the map. This was to further emphasise its importance as the residence of the lord of the manor. The open, strip-farmed, three-field structure is also conspicuous by its absence. In the Chilterns, much of the three-field system of farming disappeared before the 17th century because the land had been enclosed – a process that extinguished common rights and converted the land to private property.

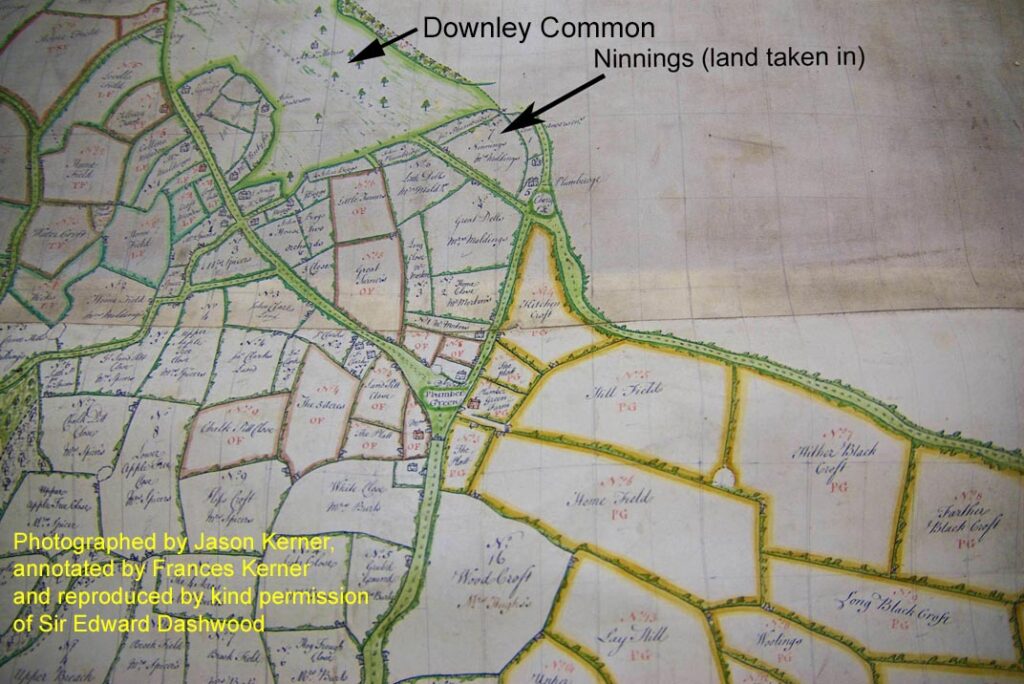

Looking in detail at the area around Downley in another estate map dated 1767 (an extract of which is shown below) there is further evidence that the area bounded by what is now Littleworth Road and Plomer Green Lane was then part of the Common. One of the fields named on the map is called Ninnings. The name first appears in 1631 when a perambulation of the Manor took place. ‘Ninnings’ means land taken in, identifying it as originally part of the Common.

In the early 1800s through to the 1860s a large number of the parishes around West Wycombe lost their commons because of enclosure. At this time Philip Rose (later to become Sir Philip Rose) was solicitor for Benjamin Disraeli of Hughenden Manor. He wrote a detailed, nine-paged letter to Lord Carrington setting out the case for the enclosure of commons. This letter (held in the archives at Windsor Castle) was reminiscent of the view of Sylvanus Taylor, who in 1652 charged that ‘The Two Great Nurseries of Idleness and Beggary etc in the Nation are Alehouses and Commons’. Philip Rose reiterated the belief that commons are places that attract vagrants, where the inhabitants are lazy and their children uneducated. He proposed enclosure of all the commons, and that the Lords of the Manor (including that of West Wycombe) should work together, which would reduce the legal costs associated with process. Commons in the parishes of Great and Little Missenden, Penn, Hughenden and Chepping Wycombe were enclosed subsequent to Philip Rose’s letter.

It is therefore surprising given that the commons of parishes surrounding West Wycombe were enclosed, that the same fate did not befall Downley Common and the other commons of West Wycombe Manor. There is no documented evidence to account for this to be the case, but a number of reasons may have played a part. These reasons include the keeping of manorial records from 1208 which were held by the Bishops of Winchester and which were purposely handed down, eventually passing to the Dashwood family in 1698; the continuity of ownership by the Dashwoods meant that no new owner came in to change the management of the estate; and the death of Sir George Dashwood in 1862 may have disrupted any possible plan to enclose the commons, which in itself would have incurred costs. Finally during the 1860s enclosure of commons started to be questioned nationally and eventually came to an end.

In 1865 the Commons Preservation Society was founded and helped to bring in legislation to protect common land. This society was to become the Open Spaces Society.

Under the Commons Registration Act 1965, Downley Common was registered as common land with 16 people confirmed as having common rights. Registration means that it is protected by law and although Downley Common historically had an agricultural function, it is now land that is enjoyed by all members of the public.