MY STORY by JOE BOWLER

Before the council and private housing estates were built around the village from 1950 onwards, Downley, being a ‘No Through Road’ village was a quiet and fairly secluded place with just two means of access and exit. One being Coates Lane, which was little more than a single track lane with a few passing places, was used mainly to serve Manor Farm, and used by cyclists and people walking to and from their jobs at the Hughenden end of Wycombe Town.

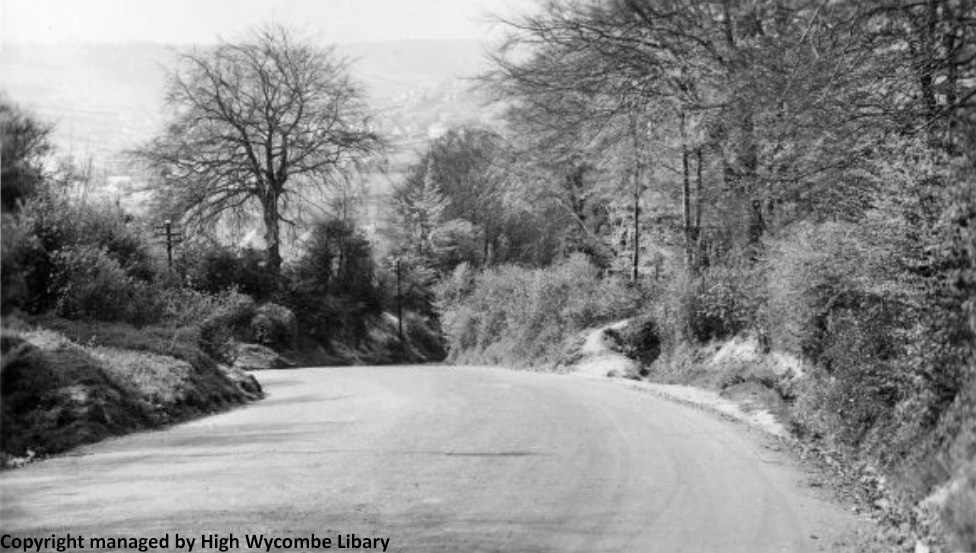

The main road into Downley was Plomer Hill. From its junction with the A40 it rose to cross the main railway line from Marylebone to Birmingham before a short level stretch, which ended at the base of the very steep and bendy hill that rose up to the village. There were three bends in the hill, each hiding the steep climb beyond it, and many is the time that drivers have had to call for help as they had not started the climb in a low enough gear. It was a general rule that standing passengers were not allowed on the buses on their way up the hill, and this was met by many grumbles by people who were coming home from work, especially if they lived in the farthest part of the village.

If there was even a small amount of snow both these roads soon became impassable, and it was not unusual for the village to be completely isolated for days on end. There are still people living in the village who can remember one winter when the snow reached the top of the hedges in Coates Lane where it had drifted, and most of the time we used to have to wait until it melted away naturally.

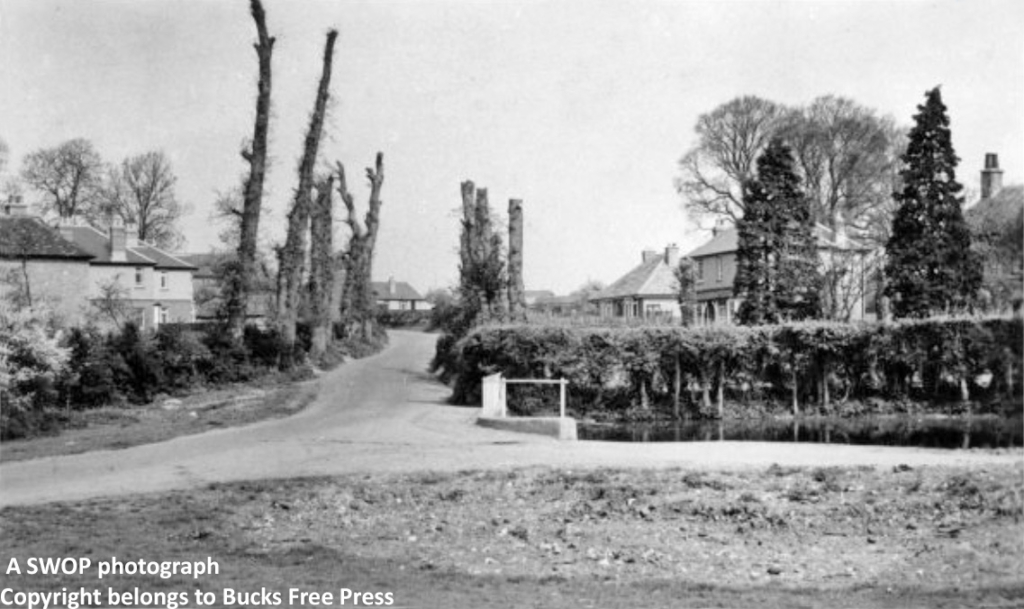

When Plomer Hill reached the summit it was faced with the village green (now known as Jubilee Green) where the road then divided into two. The left hand road was called Plomer Green Lane, and extended right up to the top of the common by the Blacksmiths’ cottages and Forge. This marked the western perimeter of the village. A small road branched at right angles across the common to serve several houses that just had a hard track in front of them. This track branched left and right, the left path leading to the Le De Spencers pub, and Stacey’s bake house.

The road to the right of the old village green was Littleworth Road, and marked the eastern perimeter of the village. This continued along as far as Coates Lane, where it joined up to the Commonside road. This, as the name implies, extended right along the side of the common until it met up with the short stretch now known as the High Street, which joined up with Plomer Green Lane and so completed the circuit of the village. I had always thought of the village as being roughly circular but now I think it is more of a drunken triangle.

For youngsters of Downley, growing up in the thirties and early forties was a Golden Age. Surrounded by grass fields, corn fields and woodland that stretched for miles, we were able to wander for hours on end, and got to know every footpath and trail, every tree that we could climb or hang a swing from, where we could find the wild strawberries that only grew in a couple of place, the sweetest and biggest blackberries, and the edible wild cherries, and where we could find the biggest hazelnuts, and even where we could dig up what we called pig nuts. This was on the common in a spot that we used to call The Glade. I’m not sure what they were but they did not seem to do us any harm. We also knew where the sweetest fruit was grown in the allotments, and where we could do a bit of ‘scrumping, with the least chance of getting caught.

One day, on the way home from school, two or three of us went to the allotments especially to scrump some pears that we had seen a few days earlier. We had just put a few in our pockets when all at once there was a terrific bang of thunder- we were all terrified thinking that God had seen us and was showing his anger. The powerful messages of the commandments was very deep in the minds of us even at the age of six.

One of the favourite areas to explore was the Common. It was not so overgrown with trees as it is now. On the banks along from Well Cottage grew heathers, pretty air bells(?) and all sorts of wild flowers, yellow furze bushes and ferns, as well as being home to skylarks and many different types of birds and small animals, so much to see.

The ‘Dells’ created lots of fun. These old clay diggings were spread over various parts of the common, some quite deep, many of which have been filled in over the years. In fact, the cricket pitch is played on what was the deepest and most concentrated area of diggings. In some cases the dells formed ponds, the one I remember best was sited on the left hand side of the road that cuts across the common from Blacksmith cottages. This had a great collection of newts, among which were the large black ones that had a frill running down the back and tail, we called them ‘Jacks’ and the smaller types ‘Effs’. Sadly this pond was filled in years ago, and I suppose those creatures have been lost for good.

Many of those ponds had names that still exist, Big Daisy, Little Daisy, and Mannings (just a few yards on to the common from the top of Hunts Hill). I’m sure I saw a hole just at the side of this pond caused by an unexploded bomb during the Second World War. I cannot remember it ever having been dug up or exploded by the military (treasure hunters beware!). Other ponds in the village were Sandpits- it may have got its name from the possibility that sand was dug from it at one time, as I do know that there are several seams of sand in the area.

Another pond in that area is Kiln Pond. Was this connected in any way with the tile making that was carried out in the village? It was always said to us as children that we must not play around this pond as there was a very deep well in the middle of it. I do know that there was a wooden walkway out to the middle, and that women would collect buckets of water from there for domestic use, so perhaps the old story was correct.

At one time, within the memory of quite a few older villagers, there was a pond where Jubilee Green is now. This used to have a tubular rail around the road side, just a nice height for youngsters to hang by the knees from, I remember finding two duck eggs on the edge of the pond one day when I was on my way to school. I know that when the council filled in this pond it caused the cellar at number 3 Plomer Green Lane to flood, and it had to be filled and capped off.

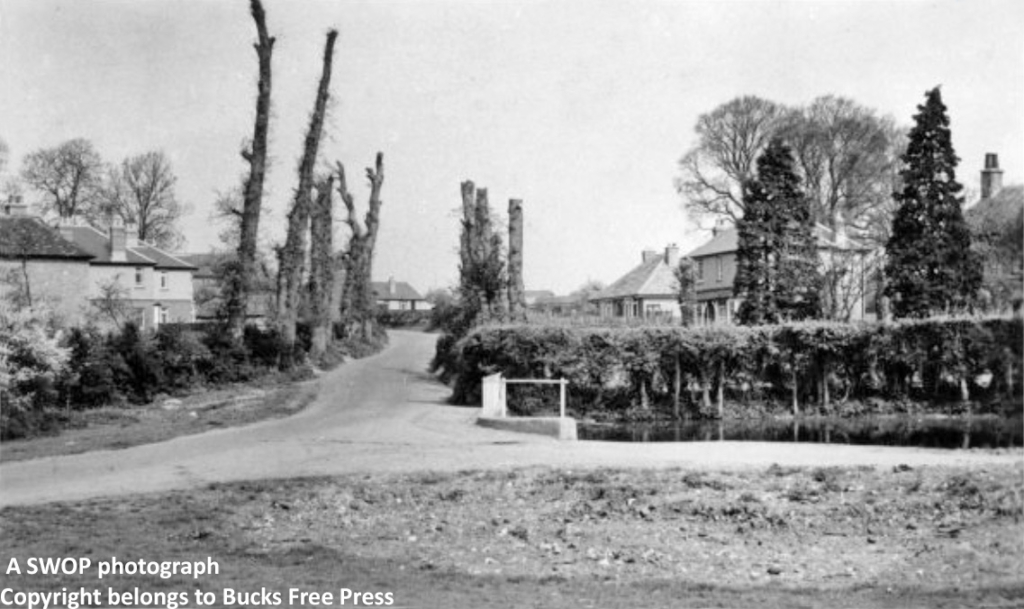

Littleworth Road, c1930

We were not aware of the hard times that our parents were having at that time. Short time working in the chair trade was a yearly event, and except for a few engineering businesses and the building trade, furniture making was the major business and employer in the area. And of course many families were still bearing the loss of the men that were killed and wounded in the Great War- so many men from such a small village.

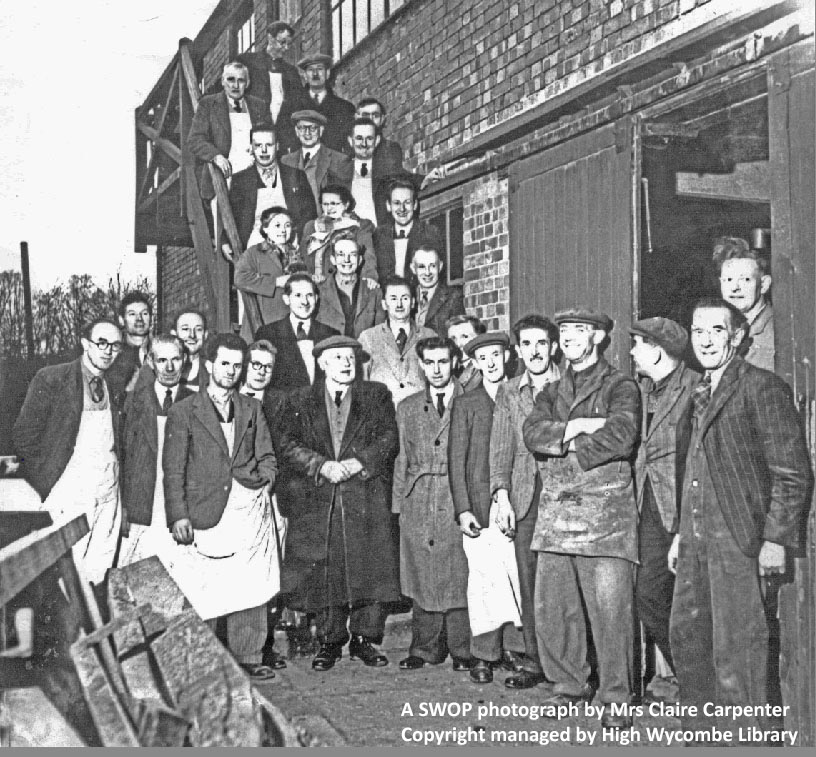

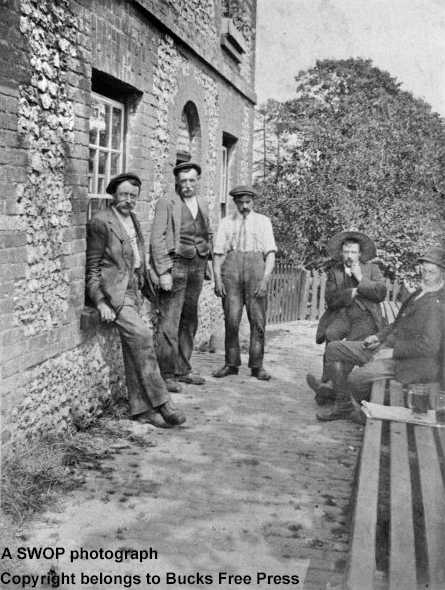

We had three furniture makers in the village with Mines and West at the top of Narrow Lane. They made high quality furniture, which I think sold in the fashionable London stores, and they employed machinists, makers, polishers, and their highly skilled wood carvers. Another firm was Norman Spriggs- everybody knew him as ‘Fiddle’. I’m sure that was no reflection on his honesty. He had this massive three story, wooden building, just behind where the hair salon now stands. When the wind blew it creaked and groaned as if it was haunted- an eerie place to be in if you were an impressionable youngster. He specialised in upholstery I believe.

The last factory was R and H Mines, next to the Old School. It was fascinating to look through the window and see the machinery working, and the wood turners work their lathes, with great showers of shavings seemingly flying everywhere. They manufactured chairs, and I can still visualise Mr Styles walking down the wooden staircase from the polishing shop with chairs in his hand ready for dispatch somewhere.

I remember somewhere about 1932 that the factory caught fire; apparently one of the pressurised paraffin lamps that they used for lighting had exploded. But it created great excitement in the village and everyone rushed to see it. What struck me as funny, and I still remember, is the spouts of water which were coming out of the firemen’s leaking hosepipe, and my concern that the school might burn down.

There were several individual craftsmen working in their sheds or workshops. My granddad used to finish of the roughly machined backrests of the Windsor chair known as a Smoker Bow. He took great pride in the finish of these and we had to take the greatest care in carrying them across to R and H Mines. I can still remember the smell of the glue pot that used to stand on the wood burning stove in his little workshop. This consisted of a metal pot partly filled with water, and the glue pot fitted down into the water which when heated up melted the cow heel glue. A piece of cane beaten flat at one end made a form of brush for applying the glue.

Another man that we all used to know well was Mr Collins who lived in what we always called Bottle Cottage, in Plomer Green Lane. His speciality was to finish the back legs of a type of chair. Why we got to know him so well was because he would sometimes have some ‘back feet’ that were not good enough to finish, but they made super runners for a sledge. A rub down with a bit of sandpaper, a coating of lard or paraffin, and they would allow you to speed down the banks of the common. We all liked Mr Collins and his wife. They were gentle and very nice folk.

Downley in the early thirties, and indeed in some parts much later, had very limited services. Water was drawn from the well, which collected rain from off the house roof, and in some cases was discharge into large water butts. When the first council houses were built semi-rotary hand pumps were fitted in the kitchens, which brought the water up from the well. For the people that moved into the new house this was a big step forward into the twentieth century. The main drainage didn’t come to the village till the middle thirties, so the waste was dispatched to a cesspit, which was collected when necessary by a lorry which we called the ‘Dirty Dennis’. For those houses without a cesspit the bucket lavatory was the accepted means of collection, the disposal of which involved all sorts of methods, open trenches across the garden covered with lime and soil, or in open pits, which in time were filled over with earth. They used to say that was where the best runner beans and sweet peas grew.

There was a man in the village that used to earn a few shillings for emptying these buckets, and could often be seen in the twighlight hours carrying two buckets on a wooden yoke- no doubt to be despatched to his own private little hole. Those bucket lavatories were sited in small brick or timber buildings; these had a small door in one side to allow the bucket to be removed. They were usually sited away from the house, and it wasn’t a very pleasant journey to make on a cold winters night. The seats were made from planed wood, mostly single-seaters, but sometimes a smaller seat especially for children would be made to fit over the larger hole. Toilet paper was made from squares of newspaper; a hole pierced in one corner and a piece of string threaded through and hung up on a conveniently sited nail. Much time was spent after reading an interesting piece of paper, trying to find the matching piece from the rest of the bundle. To secure the door a piece of string was fixed to the door and tied back to a nail on the wall. Because it wasn’t practical for everyone to go out to the ‘privee’ in the cold night air, every household had a collection of chamber pots often referred to as ‘Jerries’, which were modestly placed under the bed. It was a convenient way to allow everyone to pee in comfort, and I’m afraid that the emptying of them was left to the mother of the house. They were often emptied on the compost heap as it accelerated the decomposition- not very hygienic, but practical.

Lighting was given from paraffin wick lamps. Some were really beautifully made and they gave just enough light to read by, for seeing to get to bed. A candle was the only other means of light. So when the electricity was finally laid on and each house had a light in the kitchen and one in the living room, as well as one 15 amp plug for power, we all thought we had truly entered the twentieth century. The number of appliances that were connected to the lighting socket was unbelievable, and would have had today’s health and safety officials in spasms.

Cooking was mostly done on the kitchen range, a cast iron top on which you could boil saucepans and kettles, and a side oven from which came the most wonderful tasting cakes and tarts as well as the roast Sunday dinner. From the open front you could make the most delicious toast, much tastier than anything cooked by modern day electric toasters or grilles. The main drawback was that the fire had to be lit every morning. This needed lighting wood to start and the wind in the right direction otherwise you could get a room full of smoke. The main fuel was coal which was delivered, usually half a ton at a time, in sacks weighing one cwt., a big outlay for the family. Very often we youngsters would help out by bringing boughs back from the wood. Sometimes you were able to buy a complete tree from West Wycombe Estate. I remember our family buying one of these trees and cutting it down with a long, cross-cut, two-handled saw. The morning ended in disaster because when the tree crashed down it frightened the horse we had hired along with a cart to get the tree home. The horse reared up and charged off, tearing a wheel off the cart in its rush to get away. I can‘t remember the outcome but I’m sure they got the wood home somehow.

Trying to copy our elders, me and my friend borrowed a similar saw from the farmer Mr Cross. It was really blunt but we selected the tree we thought would fall nicely. When, after hours of sawing, the tree finally crashed down it made so much noise it really scared us and we ran off. Of course we would have been in real trouble if we had been caught, as I think the tree was suitable for furniture making.

In most houses Monday was the busiest day of the week. This was when the weekly wash was done, which meant that the copper had to be lit to boil the water this was a brick built structure which had a firebox below a deep shaped bowl, either made of copper but more often galvanised iron, it was often built next to the kitchen range and shared the same chimney. All sorts of burnable material was used to get the fire going well. I remember old shoes, cardboard etc as well as wood and coal being shoved into the firebox. Gradually the water would start to bubble, and in would go the sheets, shirts, and anything that needed boiling. The clothes were untangled with the help of a copper-stick, usually a piece of round wood about thirty inches long. This was also used to lift the washing out of the boiler, the washing then had to be taken to the sink to have the soap washed out. It was a very hard and time consuming job, particularly as families tended to be quite large in number in those days. the next problem was to get all of this washing dry and aired easy enough in warm weather but a real headache in winter, and many people will remember a series of washing lines hanging in the kitchen as well as the wooden clothes horse used for airing, this was placed in front of the fire, which could be dangerous if you didn’t keep an eye on it, but was very effective.

When the washing had been taken out of the copper the remaining water was used for other purposes, and this is a true story told to me by a villager. Her family consisted of three girls and one boy, and when the clothes had been washed, and the water in the boiler had cooled down sufficiently their mother sat them all around the rim of the boiler and that’s where they had their weekly wash down. That wasn’t the last use of the water, as it was heated up again and the week’s crockery which had been collected up was then washed in the copper.

The copper was also used to boil up water for the weekly bath. This was usually a big tin bath sited somewhere near the kitchen range to try and keep warm. This was the situation in most houses before the council houses were built, even in those for some long time water still had to be taken from the copper to the bath but this was not considered a chore to be able to enjoy the luxury of a proper bath.

Even when the washing had been dried it had to be ironed- a pair of solid cast-iron flat irons would be placed on the kitchen range to heat up. This was always a bit hit and miss and the irons were sometimes tested by a quick spit on the base. If it disappeared too quickly the iron was too hot. A thick cloth was wrapped around the handle as this was the same heat as the iron base. An electric iron was one of the appliances that were sometimes connected to the light socket when the electricity had been laid onto the house. The sheets etc were then ironed on a wooden ironing board, just like the ones that aroused today. I often wonder how the women managed to survive in those days and in the years before. Every job was hard work- cooking, cleaning, and washing. They had so little rest it is no wonder that they looked old before they were middle-aged.

Large families were not unusual in those days, and counting up the number of children that belonged to the parents that lived in the twenty-two council houses in Littleworth Road came to roughly eighty-nine. Of course many of the older children had left home, married, or the girls most likely ‘in service’. This happened frequently to relieve the pressure of overcrowding in the small two bedroom cottages that was the normal accommodation in villages. If they were lucky they would have a kind employer, but often they could be treated little better than slave labour, and if they stepped out of line in any way, such as being a few minutes late in returning to the ‘Big House’, they would be dismissed instantly and thrown out of the house regardless of time or weather.

One of the strange things was that most of the men were very rarely called by their proper name. In our house there was a Flattey (Fred), Mitchel (Stan) and Joller (Robert). Going along the houses in Littleworth Road was Wiff, Gedall, Chummey, Nobby, Domby, Aggle, Sugar, Happy, (I can’t remember the Sextons nicknames), Paint, Dick, Drummer, Dibby and Chewy. That was most of the names in the first twelve houses in Littleworth Road, and this was repeated all around the village.

By the old Bricklayers Arms, (which stood where the grass area outside the dog beauty parlour now stands) the road turned at right angles to join, what is now known as High Street, and continued to join Commonside. This basically forms a circle of most of the village. Once when some councillors were visiting to inspect some proposed work in the village one of the party said to my granddad “Joe, I reckon Downley must be the asshole of Wycombe”. Granddad always proud of Downley replied,” Well, and you have just passed through it” – a brilliant cut down I think.

As I walk around the village I often think of the people that lived in the houses that I am passing, and of incidents that may have taken place. In the first cottage in Littleworth Road lived Mr Brooks. A painter and decorator by trade but in his spare time a very talented artist- his paintings of different places around the village were eagerly sought after.

I lived at number1 (now 18) Littleworth Road. We had a clear view along to the old farmhouse and the big barn, and often we would open the back door, which was only about three feet away from separating us from the field, to find a horse’s head almost reaching into the doorway, or some cows hoping for a snack of some sort. One day we even had a deer looking in at us. The fence on either side of the road was an avenue of giant elm trees, and many of the men who served overseas during the war said that those trees were one of the things that most reminded them of home. We used to have succession of people calling at our house as granddad was a Parish and District councillor as well as being involved with the local hospital and the village cricket team etc. He worked very hard for the betterment of the village and its people.

Going along the road from our house was Mrs McCarthy, known to everyone as ‘Mac’. She took in washing, I suppose, to help with the family budget. She also would be called on to prepare people after they had passed away. It saved money by not using the undertaker. She was a happy go lucky woman and very popular in the village. Very patriotic too as I remember on VE night she was doing hand stands showing her large bloomers on the back of which was fastened a union jack flag.

At number 3 lived Mr Langley- we used to take our clocks and watches to him for repair. Further along was Mr Rupert Sexton, a tall man with a long moustache, who was still delivering slow spinning balls for the village cricket team at the age of 62.

Next door lived the Stallwood family; the tales told about them would make a good novel on their own. Head of the family was known to everyone far and wide as “Paint”. He was only about five feet high, but tough as old boots. Apparently he couldn’t read or write but he ran a very successful greengrocery business from a woodshed in his back garden and many a housewife was glad to go to him for six penny-worth of pot herbs, which consisted of one each of onion, swede and a turnip. He had a large round of customers, all of the village, and up to Naphill and Walters Ash. To do this he used a flat bottomed cart about ten foot by four, which had an apex-type canvas cover which stood about three feet above the bed of the cart. Wooden crates were laid at forty-five degrees along both sides of the cart, filled with all sorts of vegetables, fruit and potatoes. One of the tales told about him was that he would say “I’ve got some lovely tomatoes today mam, but, I wouldn’t advise you to buy them”.

The cart was pulled by a lovely old horse (maybe a Welsh Cob). Ginger in colour it seemed to know exactly where to stop for each customer, and would like to have a little fast trot along Commonside at the end of the deliveries. Mr Stallwood liked to chew twist tobacco and people reckoned that he would turn round looking along the length and could spit so far as to go past the back of his cart. I had many a ride out on those rounds, and to a young lad it was a bit like riding in a prairie cart in the Wild West. There is very peaceful feeling sitting behind a gentle horse when it is just ambling along.

Mr Stallwood also used to have another small business, which was to deliver the Sunday papers. Although he couldn’t read he used to like to look at the pictures while having his breakfast before delivering to his customers. Granddad used to get mad because every page had grease on them. I can’t believe the story that he laid in bed with an umbrella up because the roof was leaking, but who can tell. His son Jack was another who had many tales told about him. I remember hearing a fire engine passing our house very late at night, and next morning the rumour was that Jack having put the horse in a new stable at the top of Coates Lane, thought that it might be frightened of it’s new surroundings, so he lit a candle and placed it on a ledge along with a comic for it to look at. Sadly the candle fell down onto the straw bedding and the horse died in the flames.

Another story that I think must be taken with a pinch of salt was about the time that Jack went to volunteer for the Territorial Army. They asked him if he could shoot a rifle, to which Jack said yes. They had a .22 rifle range at the barracks in Suffield Road, and the “butts” were at the base of Tom Burt’s hill. With the targets all prepared the instructor told Jack to fire at the bull. Now, there was a herd of cattle on the hillside, amongst which was a bull, so when the instructor said “fire” Jack did, and the bull fell down dead. I don’t know if this story is true, but it would not surprise me to learn that it was.

At number 12 lived the Styles family; one of the houses where we youngsters were always in and out of. On the back of several doors would hang long lengths of cane that Mrs Styles would use for caning chair seats. She was an expert caner, as were many women in the village, and it was one of the chores of the Styles children to take the finished pieces down to Vere’s factory in Chapel Lane, and to bring back more for their Mum to work on.

Next door in a small bungalow lived Mr and Mrs Harris, I remember her because at certain times of the year she would make Ginger Beer. We would take an empty bottle along and a few pennies for a refill. She and Mrs Styles were also very good card players.

Further along the road was a wooden store owned by Mr Styles. He sold most general items of grocery, soft drinks and cigarettes and tobacco. One day a few of us had saved up some money and thought we would try some cigarettes, telling Mr Styles that they were for one of the boy’s dad. Mr Styles quickly realised that we were fibbing, but thought that he would teach us a lesson. He said sorry but he hadn’t got the cigarettes that we had asked for, but knew that the boy’s Dad likes a tobacco called Black Beauty. One of the strongest tasting brands, he said with a packet of cigarette papers to go with it, the boy’s Dad would be satisfied. We all went down into the wood and quickly rolled up a cigarette each. It wasn’t long before we were turning green and feeling like death. It was then that I realised why Mr Styles had been smiling as we went out of the shop.

There used to be a shop on the corner by Peter’s Cottage. This had several owners over the years, the last one was Roger Smith helped by his wife Cathy (she also used to play the organ at the Methodist Chapel in Chapel Street). Again this was a general store (the original convenience store) and it formed a very dangerous corner and was demolished sometime after the war. I remember Peter who lived in Peter’s cottage; I suppose that is how it got its name. He was a small stocky old man, with a long beard. I know that the chimney of the cottage was struck by lightning one day, but Peter had a lucky escape as he was sat on the ‘privee’ in the garden at the time.

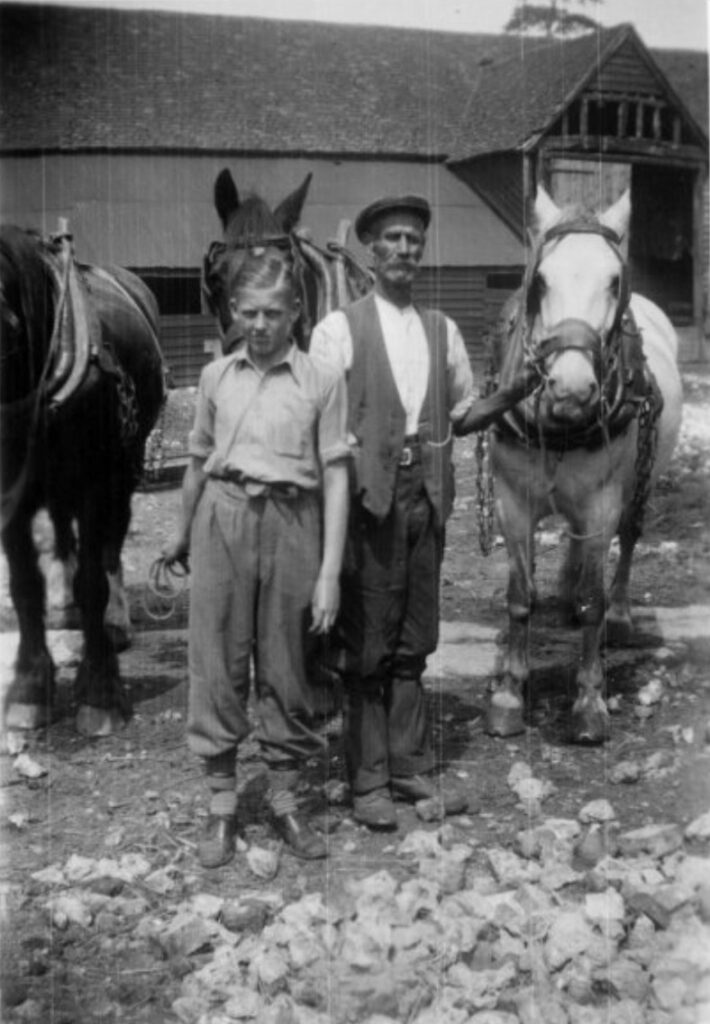

In the early forties Mrs Coburn, who lived in the house adjoining the shop, ran dancing classes for the local girls, and we boys would take it in turn to look through the letter box. When the word went round that Norma was doing the splits there was a mad scramble to get a look. At the top of Coates Lane was a small workshop owned by a Mr Mullet that was used for something to do with furniture, but I can’t remember much about it. On the opposite side of the road was a long cottage which was owned by Mr Smith. He was the ploughman for Mr Cross, and I can see him now ploughing the fields where the houses stand between Hithercroft Road and The Pastures. He used two massive horses, a black Shire and a brown Clydesdale. He loved those horses and must have walked behind them for hundreds of miles in his time at the farm.

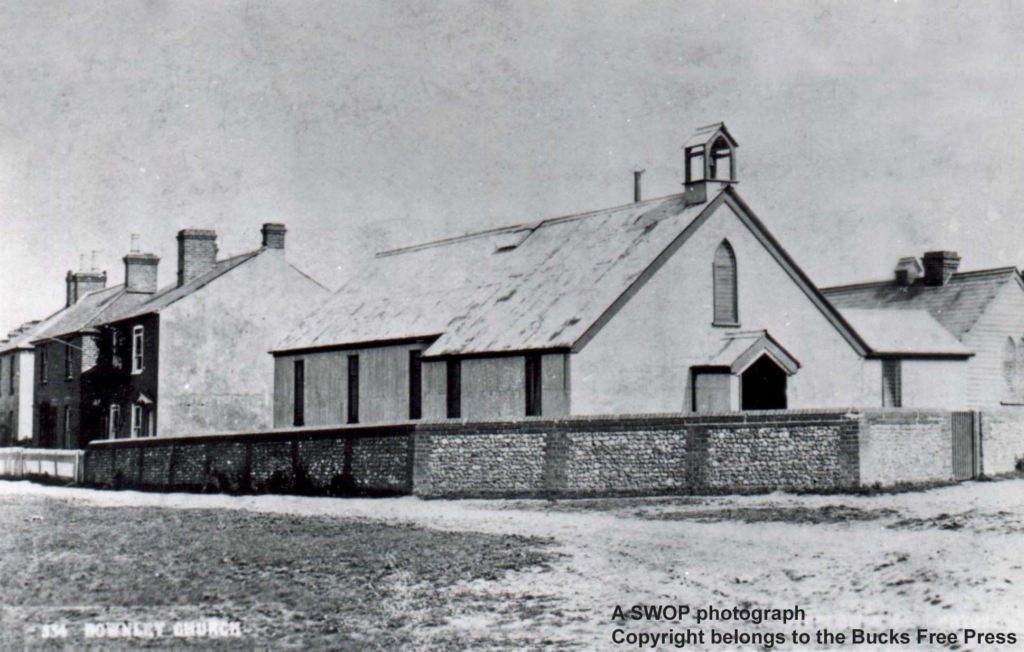

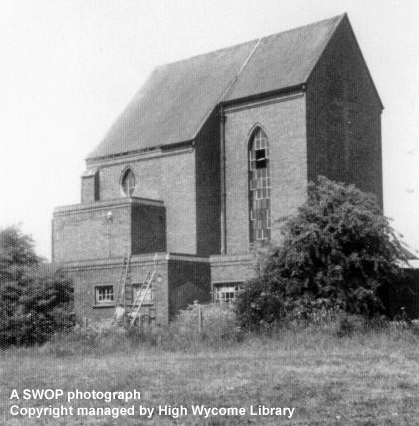

At the common end of Narrow Lane stood the old ‘Tin Church’. This was a Church of England church and had its own Priest in Charge, Tommy Campbell. He was very popular with all the lads and had a good congregation- somewhere about is a photo of me and Jim Mullet stood at the entrance to the church dresses in our cassocks and surpluses.

Mrs Cooper was the caretaker, and also the bell ringer, and the story is told that the bell rope was that long that she could walk the full length of the aisle dishing out the hymn books while still ringing the bell. Also she could walk outside the church door to see if there were any latecomers still tolling the bell. She was a faithful member of the church and very highly thought of. After Mr Campbell left the village there were several temporary visiting priests. One I remember was a Mr Nash. One Sunday afternoon we were singing some hymn when one of the boys deliberately sang a high note when it should have been a low one. Reverend Nash dashed down the aisle and gave the boy a hard smack around his head. One of the Sunday school teachers, a young Mrs Green, gave him such a strong dressing down, saying he should be ashamed to treat a young boy in such a manner. I don’t know how far the complaint went, but I can’t remember seeing him at the church again. It was a sad day when they closed the old church down and started to build a massive church in Plomer Hill. This was only partly completed when the war started and some time later a fire started which burned down the wooden wall which shielded the completed part of the church. Eventually it was demolished and the present church was built on the same site, a much more practical building for the area, and well used by the different faiths.

Somewhere at the back of the cottages facing the common used to be a small blacksmith’s forge. The owner specialised in making hand tools for the woodworkers in the village, and it was said that you dare not leave anything made out of iron outside your house at night, as next morning it would be gone and probably turned into a chisel or another useful tool.

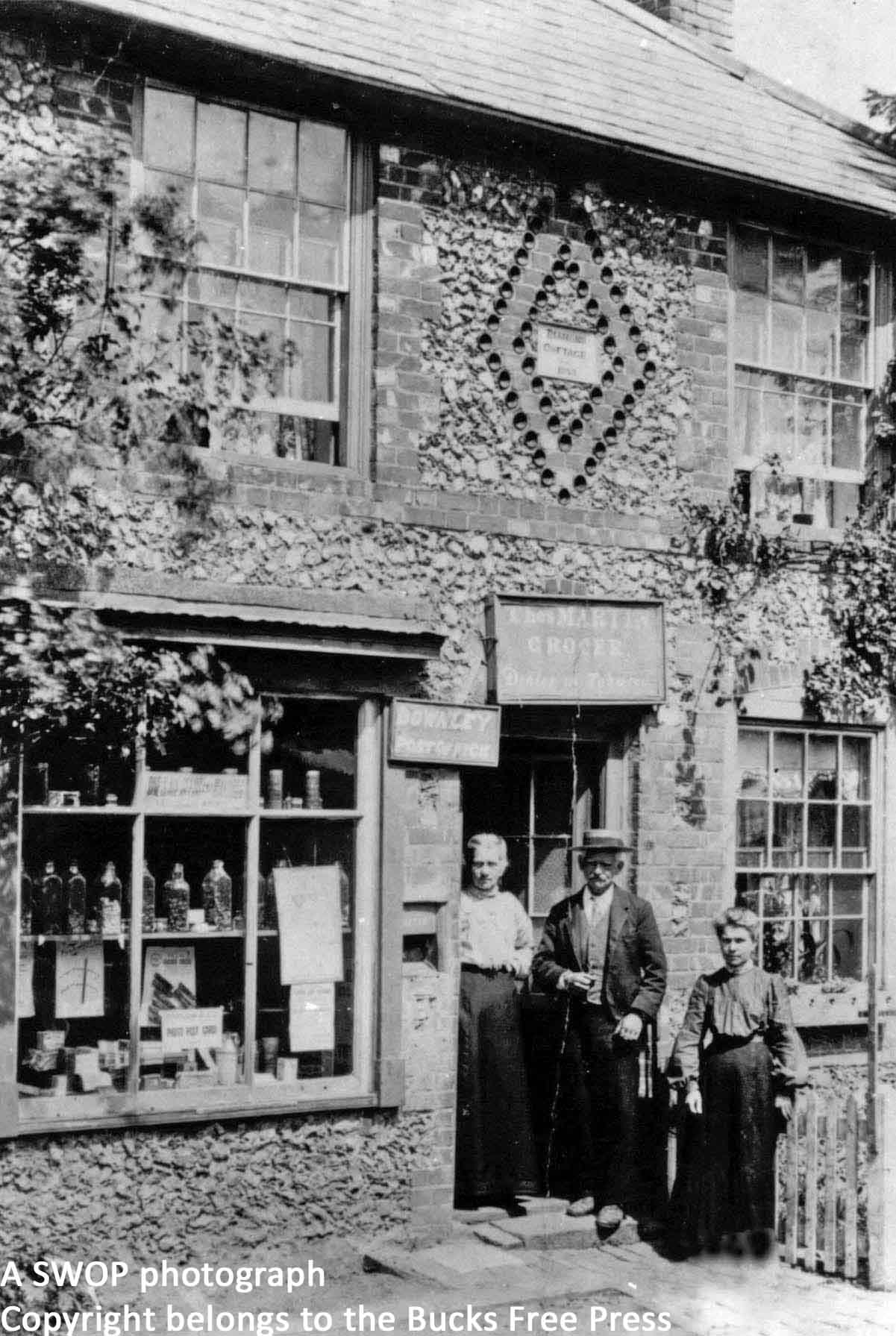

There used to be a shop along Commonside that has long ceased to be used for that purpose. It was in the ‘Pink House’ that the late Joe Pidgeon used to live in. It was run by Mrs Mines, the wife of the furniture factory owner Mines and West. It was a grocery shop and tea importer. I’m sure there is a photo of this shop around in the village. Mrs Mines also used to run a clothing business and employed several local women and young girls as seamstresses.

Just before the shop above lived Mrs Smith, one of the West family. She employed quite a few local women who sowed sequins on expensive dresses that were bought down from the fashion houses in London. This was a very skilled job, but I doubt very well paid.

Where number 3 Commonside is now used to be a sweet and tobacco shop, also selling all sorts of useful items- paraffin being one of them, and we would often buy a bottleful to put on the sledge runners. I remember that there used to be two slot machines outside of the shop- one to buy cigarettes, and the other to buy a small bar of Cadbury’s chocolate. The first person I remember owning the shop was Mr Bond. I remember this because some of the older boys let the brakes off of his car and rolled it down the bank of the common. The young lads weren’t little angels in those day.

Moving along the road a few yards one came to the centre of the village, there was the Methodist Chapel at the beginning of Chapel Street. This is where quite a few of us youngsters went when the little tin church shut down, and where quite a few of us were married in later years. It was supervised by a circuit minister, a full time position, but mostly served by local lay-preachers, who ran the classes for young children and took the services. It was quite a happy place to go, and much less formal than the old church.

Next door to the chapel lived the James family. Mr James repaired watches and clocks as a hobby. He was known as ‘Cold Wind’ because regardless of however warm it was, when people said to him “Good day Mr James, lovely day” he would always reply “Yes it is but there is a cold wind”. Quite a few of the old Downley families lived in Chapel Street- the Smiths, Youens, Mines, and Bristows. There is a wonderful picture somewhere in the family of old Mr and Mrs Bristow celebrating their Diamond Wedding with all their children and grandchildren shown in a large group outside the village hall.

The school was at the top of Chapel Street, and the children went there from the ages of four to fourteen. It wasn’t till about 1938 that the new school was opened at Mill End for 11 to 14 year olds. I remember my first day at the school, so many children running around shouting with excitement. One thing still sticks in my mind was Dave Youens running around the playground in circles, arms outstretched making out to be an aeroplane- the real thing was a rare sight in those days. The teachers that we had still stay in my memory. Miss Brown teaching the infants, she became Mrs Church on being married. She cycled all the way from Lacy Green every day and was a much loved person. Even in old age she remembered the names of all her old pupils. There was a Mrs Brown who took the next age group and then a Miss Thomas – a very attractive, dark haired, Welsh lady who I’m sure caused some initial stirring of the hormones in the older boys. Mrs Meadows took the fourth year pupils and served the school for many years. She was quite strict, but well thought of. Finally in the last year the Headmaster Mr Avery took the classes. He taught all subjects and such sport as we were able to play. He was definitely a teacher of the old school, demanded good manners and obedience, and was much respected for it.

On the opposite side of Chapel Street to the chapel was a wall that ran round two cottages- one either side of a pub called ‘The Golf Links’. They were all joined up in a row, and were demolished about 1933. The cottages were only two up and two down with a landing at the top of the stairs. At one time they were occupied by the Bowler family and the Sextons. They both had quite large families and it must have been a real headache to find room for everybody to sleep. They must have had very low ceilings, as I remember when the Hall family lived there their son Peter was ill in bed and the local priest Tommy Campbell took him a book which he was able to pass up to Peter balanced on the end of his walking stick. The pub was run by Tom Gallnut and his sister Sarah. There was also a brother Harold but he worked elsewhere as a chauffer I think.

The next shop was owned by Mrs Spriggs, and again was a general store, but she also used to sell shoes and boots, and some everyday clothing. The shop was a delight to visit. There were big round cheeses which were cut with a wire attached to a peg at either end, not an easy task. There were rows of little wooden drawers, containing all sorts of goods, buttons, cottons, tobacco, needles. She would sell practically everything that one would need, and I think had been very generous to people who were going through a bad time. She was also a generous supporter of the little ‘Tin Church’ which stood at the top of Narrow Lane, and was very sad when the church authorities decided to build a monstrous great church outside the village boundary.

She always employed a schoolboy to deliver the groceries to her customers. It was the best job for a boy in the village, and when I managed to get it following Bob Langley I was really pleased and did it until I left school. The wages were five shillings a week and a bag of peppermints, and for this you had to be there every evening and Saturday mornings. The round stretched all around the village and across the common to the houses beyond the Le De Spencers pub. There were no deliveries on Tuesdays but on that day you had to chop enough lighting wood for the rest of the week, and clear out the weeds between the black bricks that made up the footpath, and there were a lot of them. I really disliked that job.

To help carry the groceries I made up a trolley, made up of four pram wheels- the front pair fitted to a piece of wood that swivelled on a centre bolt, and for guiding I used an old pram handle. This was much better that the usual rope handle. I used to enjoy the deliveries to the top of the common because on the way back I could start off from Blacksmiths Cottage and freewheel almost to the top of the hill leading to the High Street.

My last delivery on Saturday morning was to Tom and Sarah Allnutt who lived in one of the old cottages (where the footpath sign is at the rear of the bungalows leading into Plomer Green Avenue). By this time I was starving hungry, and Sarah would always be dishing out a shepherd’s pie. It smelled wonderful and my mouth still waters at the memory of it.

Mr Jim West had the butchers shop, and it fascinated us youngsters to seethe great sides of beef being carried in to the cold cupboard. Sausages hung on rails, and at Christmas time he always used to put a pig’s head with an orange in its mouth in the shop window. It seemed a very scary thing to me. He was one of the few people in the village that had a phone at that time, and I seem to remember that he had a nice little sideline as a ‘runner’ for a bookmaker. People would pop in with their bets written down and he would ring them through. I suppose it must have been profitable. He also owned the ‘Mountjoy’s Retreat’ pub in Moor Lane. His sister Pearl looked after this and I think most of the village lads had their first drink there. There was a type of pianola in the ‘big room’, which played tunes printed on a revolving drum. I think you had to put a penny in a slot to make the thing work, but I seem to remember that it only played one tune, ‘In a Monastery Garden’, which after a while got pretty boring.

At the rear of the pub was a slaughterhouse. Villagers would take their pigs there to be dispatched. It all seems a bit medieval now the way it was carried out. First the pig was stunned or shot with a special gun, then it was strung up by its back legs and its throat was cut to release the blood. it would then be laid on a bed of straw which would then be set on fire to burn off the pig’s bristles. It was then moved inside for preparing for salting, or to be smoked, depending the owner’s preference or of course to be carved up for sale in the butchers shop. There were just a few people in the area that could salt a pig successfully; this required a lot of skill time, and patience.

Mr West’s brother, Billy, also lived at the pub. He had lost the lower part of his left arm, presumably in the First World War. He was the assistant gamekeeper for the West Wycombe Estate and patrolled mostly around Branch Wood and Cookshall area. Of course this patrolling interfered with the local men’s necessary sport of catching rabbits- a good meal and cheap when times were hard. Now Billy liked a game of dominos. So once a week a game would be arranged in the Mountjoys, and fixed for the time that Billy had his mid-day break. The players would let Billy win quite a few games, keeping him occupied a bit longer that he should have done. Meanwhile a couple of the gang would be round the woods catching as many rabbits as possible. After dumping the rabbits in a safe place, they would arrive at the pub just before Billy realised how late it was. Apparently this little ruse worked for some long time, but Billy was no fool and as long as the practise didn’t get out of hand I’m told he turned a blind eye.

With a mate of mine, Bob Langley, we decided we would try catching rabbits with a ferret. So we saved up half-a-crown (12½p) and bought a nice young ferret and, with some nets borrowed from Bob’s dad, we set off to the banks just on the edge of the wood which led up to Hughenden Manor. We carefully fixed several nets over the burrows and took the ferret out of the sack and placed it in a burrow. At first it just played about turning head over heels, and running around in circles. Eventually we managed to get it to go down a burrow, and we waited full of excitement for the rabbits to run out into the nets. We waited and waited but we didn’t see one rabbit, and we never saw the ferret again either.

Next to the butchers shop was The Bricklayers Arms. This filled what is now the grass area, and Canine Kutz shop- a very old building, surrounded by a brick wall adjoining Plomer Green Lane. There was a raised cobbled path at the front about a foot or more high, and a couple of steps leading up to the doorway, a dodgy exit if anyone had a drop too much. The landlords were Mr Dixon and his wife, known to everyone as Bella. She was a very good business woman and even up to her latest years seemed to know everything that was going on in the village. They took over the new Bricklayers Arms when it was built and ran it successfully until well after the Second World War.

In the early thirties the only buildings on the opposite side of the road to the pubs and shops were the Memorial Hall and Prospect Cottage which faced along the common. This was where a Mrs Harris lived. She was known as ‘Mrs Lookout’ as she always appeared to be twitching the curtain slightly and ‘looking out’ to see what was going on. Mr Harris was the first person in the village to have what was called in those days a ‘wireless’. These were powered by acid batteries and needed a long aerial to receive the radio waves. It usually stretched over the longest length available in the garden, and I was told that some villagers were so convinced that this aerial would so upset the weather that it would cause it to rain all the time. Eventually when the wireless was accepted, Mr Harris used to charge the batteries for the local people. I think that he also organised an orchestra of local people. I seem vaguely to remember it playing in the village hall. it consisted mostly of string instruments.

The other building in the High Street at that time was the War Memorial Hall, built in 1923 and dedicated to the men of the village who had died in the First World War. It was a tremendous effort by the residents of the village to save the money for the building, and it has served the community well since its inauguration, more on this later. The two shops and two houses were built in the later part of the thirties, and this completed the ‘infill’ of that side of the High Street.

Before we wander too far around the village we must look at Moor Lane, known in the thirties locally as ‘Bugs Alley’. The cottages were in a bad state of repair, a row of backyard bucket lavatories in the garden. Now with careful renovations and modern facilities they are very desirable properties. At one time there was a communal wash-house on the opposite side of the road, a great place for a village gossip. Also the last cottage was the first post office in the village as well as a small convenience store. It also had bottles built into the front wall, and I wonder if it was built by the same builder as ‘Bottle Cottage’ in Plomer Green Lane.

I must mention Moor Cottage, which has ‘lots of character’ and is how the estate agents like to describe these old houses. It is reputed to be the oldest house in Downley, and I would not like to dispute that also. The other old house is ‘Old Tiles’. Whether this had any connection with the men that had a kiln for tile-making in Moor Lane I’m not sure. They must have been responsible for the pits that used to be sited in various places on the common.

The next buildings were the Wesleyan Chapel and the houses on Butterfly Bank. The modern looking houses in between were built in the late thirties, and one pair after the war. Vale Cottage and Well Cottage are on the opposite side of Butterfly Bank and are quite old although I do not know the dates. Well Cottage has a really deep well in the garden and was a godsend to the villagers when they suffered a long dry summer. At such times a local smallholder Mr Jack Spriggs would go to the water board station in Mill End Road with a horse drawn water tank and bring it unto the villagers. Somewhere in the village I’ve seen a picture of Mr Spriggs with his horse and water tank. It would be nice if it could be found.

Vale Cottage was always owned by someone ‘Posh’. In the thirties and forties a Mrs Neynoe(?) lived there. She was a governor at the school, and during late summer we would be taken out of school to go into her orchard and pick up ‘Windfall’ apples. Apart from the ones we ate I really do not know what happened to them, but I know that we always had to show her the utmost respect.

Further up the common was ‘The Steam Bakery’. It belonged to Mr Faulkner but was run by Mr Fred Langley. There are few more mouth-watering smells than newly-baked bread and many is the time that our little gang clubbed together to buy a cottage loaf then sit out in the common and scoff it all up. Mr Langley had quite a large round in the surrounding area and made his deliveries in a peculiar little van, which was like a three wheeled motor cycle with a covered body. It is the only one I’ve ever seen and would be quite a trophy for a classic collector.

Apart from the houses and the bungalow next to the lane that leads to ‘California Holdings’, all the houses are originals- the oldest being ‘The Le De Spencers Arms’, which also had a bakery in the rear part. In the thirties it was just a beer house, and there were only two small rooms for the people to drink in. The room next to the common was a private room then, and was known to the pub locals as ‘Ruby’s courting room’. Ruby was the daughter of the landlord Mr Stan Batts. He also had a son and the family were tenants for a long time. The bake-house was run by Mr Stacy and his son Jack. They also had a good round of regular customers.

Coming back to the village, in the first house past the old pub lived Mrs Cross. She was a lady that a lot of people went to when they had a death in the family as she would do what was known as ‘laying out’. That was washing and preparing the body before it was placed in the coffin- an unusual but a very necessary task. People that had died were normally kept at home in those days for a period of some three to five days before the burial. Downley was divided by two parishes- West Wycombe and Hughenden. Persons from the Hughenden Parish were buried in the Hughenden Church graveyard. They would have to make their last journey down through the valley from Common Wood and pass by the Manor House, then to the cemetery, or via Coates lane and Hughenden Road. A poor person would be taken by a horse and cart probably borrowed from the local farmer, or carried manually by friends. I can just remember the last horse drawn hearse that came to carry someone in Littleworth Road. A Mr Grey is a name that sticks in my mind but I couldn’t swear to this being reliable. There were two big black horses, complete with feather like head dresses. To a little boy of five or six they seemed massive. The hearse was shiny black with glass windows all round, and very impressive.

For the people in the West Wycombe Parish their last resting place was in the graveyard at St. Lawrence Church, ‘The Church on the Hill’. Their journey in the old days was made by horse and cart by way of either the Blacksmiths Lane route, or Kiln Pond, following the path down to The Pedestal at the junction of the Aylesbury-Oxford Road, and through to West Wycombe Village, and then the long climb around the hill and up to the cemetery. When a person was unable to afford a cart, the route was the same for the people carrying the coffin, but then they would turn along the road to Flint Hall Farm where a public footpath runs to about halfway up the hill. One of the old villagers, Mr Joe Langley who used to live on Butterfly Bank, said that he had taken part in a team carrying a coffin to St Lawrence churchyard. I don’t have any reason to doubt his story.

Where Greys Lane starts there used to be the tiniest pair of cottages in the village. I remember looking at the bases when they were demolished and they didn’t seem any bigger than a small garden shed, but they housed two families, the Redrups and the Styles family. Mr Styles was blind, and was known throughout the village as Blind Charlie though this was not meant in any unkind way. the family was very religious and could be heard chanting texts and verses at all times- a little bit scary for young impressionable children. In the same area was my granddads smallholding, about half an acre from memory. In it was a magnificent Victoria plum tree, a Bramley apple tree, as well as all sorts of small fruit trees, and a good sized vegetable garden. There were lots of chickens and occasionally geese that used to chase anyone round the large pen should they wander in there. One of the pleasing things was to sink your hands into the storage bin- one half held wheat and the other half corn, and just let the seeds trickle over your hands. It just seemed so relaxing. It was also quite a thrill to see the young chicks running along after their mother hen, and sometimes a brood of chicks would appear from somewhere where the hen had hidden her eggs in a secluded part of the plot. That was a sort of bonus I suppose. There was also granddad’s little workshop which I have already mentioned, full of special tools for chair making and always a fascinating place to visit as a youngster.

At number 47 lived Mrs Kearley. She ran the post office and the local telephone exchange- she knew everything and everyone in the village, and it could be areal gossip shop. A Miss Beryl Plumridge and her mother also lived in the house. Beryl taught the piano to quite a lot of the local children, and I suppose this brought in some income and she was very well liked by her pupils. At number 38 at the time of this story lived Mr Mendy (Fadge) to everyone, and he ran a small butcher’s business from there. All I can remember is the big, three-legged, butcher’s block that he would chop the meat on. Eventually he built a house on land at the bottom of Narrow Lane, which once formed part of Littleworth Common.

The houses that form School Close were built around 1937. I think that they cost around £450-£500 at that time. Built by a Mr Newell, known to everyone as ‘Hopper’, they still look as good today as when they were built. Opposite School Close lived Mr Hayter. He was an excellent carpenter and had a very good woodworking business. He also ran a smallholding that took in what is now Plomer Green Avenue. I can remember his mother sitting outside the house selling toffee apples. It’s funny what small incidents stick in your mind for years.

This journey around the village stops at the village green and the old farm. The green was much bigger than the present grass patch. It had a nice seat on it, which was placed there just after King George V’s Silver Jubilee. A pond used to be where the present Jubilee Green is now. It had a low concrete wall along one side (just the right height to have a sit down). A tubular railing was set into this wall, and it was a great plaything, swinging and hanging by your legs. Silly little games but enjoyed and remembered by so many.

and Littleworth Road, 1930

The farm dominated the entrance to the village- a tall, black, boarded structure about sixty feet long, divided in to different sections, mostly used for storing hay and cattle feed, and one part where a small engine was used to drive a machine that chopped up straw, and sometimes mangles for winter feed. Another small section was used to house newborn calves, and it was always distressing to hear the mother cow crying out for her baby calf when they were taken away.

In the farmyard was a stable which housed the two big horses and a small pony which was used to draw the milk float. I spent many a time riding in this float with Mr Cross, also at times with his son Ken. It would be fitted out with two large milk churns which must have held at least five gallons. then there would be a smaller container which held one gallon, and two small measuring cans one holding one pint and the other half a pint, with which you would fill the jug or container usually left outside the front door with a cover over to keep off the local cats or birds. Eventually these were replaced with bottles and the float was filled with crates of milk. It was more hygienic I suppose but seemed much less personal. One of the drawbacks with bottled milk was having to collect the empties. Some people left them nice and clean but some could be green and smelly with dried milk around the neck. A horrible job, and to this day I make a point of washing out everything that has to be collected, bottles, jars, tins etc.

The dairy was at the back of the barn on the other side of the farmyard, the cows were fitted, up into halters which held their head steady, and feed was placed in a trough for them to eat while they were being milked. The trouble was that as fast as food went in one end it came out of the other and unless you were very careful walking along the gangway between the two rows of cows you could soon be covered.

Until the late thirties, when a special milking parlour was installed the cows, were all milked by hand. Mr Austin (known to everyone as Joby) was in charge of the cows and dairy. I can see him now, sat on his little three-legged stool peaked cap turned front to back, milking cow after cow by hand, a really laborious job. The milk was then put into a container which allowed the milk to run over a water cooled corrugated panel and then into a churn or container where it was hand filled into bottles. Each bottle was fitted with a cardboard top which had a punch-out centre for opening. The returned bottles were washed ,again by hand in a big sink of hot water, a brush was used to clean the inner part, it was then rinsed and turned upside down to drain and dry. It all seems a bit unhygienic by today’s standards but I can’t ever remember any illness being caused.

There was always great excitement at harvest time. The cornfields would be cut by Mr Smith and his two horses. Then it was collected by another machine that scooped it up in sheaves and these were stacked up in ‘stooks’, which was about six sheaves, stood up in the shape of a wigwam. When these had dried they were then taken by horse and cart to an area near the farm for threshing, that is shaking the corn seeds from the corn ears. This was done by big box-like machine, where the sheaves were thrown up onto the top of it and a man pushed it down into the working part. The seed would pour out into sacks, and the stems stacked in ricks. All this was powered by a massive steam engine, which had a large wheel around which a thick belt was fixed to drive the threshing machine. It was all noise, smoke and steam, and very exciting to youngsters. The threshing equipment was worked by a special gang of men. They lived on the site in a wooden van which was towed by the steam engine at the back of the threshing machine, and they moved from farm to farm during the season.

Another great event was when the hayricks were dismantled. Gangs of us would wait with great excitement as the rick got lower and lower when, almost as if they had been given a signal, dozens of mice would come charging out, running all over the place, and all the boys and men would be armed with sticks trying to kill as many as we could. The dogs would be going berserk chasing the mice, and would be a job to calm down for days. It was during one of these occasions that I found out that mice can turn by their tail. I caught one and held it by its tail intending to drop it into a small pond to see if it could swim. It turned up on its tail and gave me a nasty bite, and yes, they can swim.

A local greengrocer, who also imported bananas, used to take his banana stems up to Mr Cross’s field, where they would rot down as compost. But there would always be a few bananas left on them, usually black or rotten but sometimes edible, and when we saw the greengrocers van appear the word would quickly go round “the banana lorry is here” and there would be a scramble by those boys in the know to get across to the heap to see if there was an edible banana to have.

Mr Cross was a character, always had time to chat and had a cure for every illness. Once I caught an infection of ringworms which was prevalent at school at that time. It showed up as a red ring of small spots on the neck. Of course he had a cure for this as well so I went along to the farm later in the day with a small bottle into which he poured some strong smelling foamy sort of liquid. “Take this home boy” he said and put some on a piece of rag, “and rub it on your neck tonight”, which I duly did. As soon as it touched my neck I nearly shot through the roof, it stung like mad. Next day when we asked him what it was he told us it was horse liniment, but I tell you this, it cleared up the infection and I never had anything like it again.

Around the area of the farm and pond were two more smallholdings. Ings Farm, which is now 2 Plomer Green Lane, had land that took in all of where Jubilee Road and School Close and the old school field stand. The other one was ‘The Elms’. I can’t remember much about this except once I collected some skimmed milk from there so they must have had some animals.

Downley seemed to attract quite a few aeroplanes that were in difficulties in the thirties. I remember one just missing the top of the elm trees in Littleworth Road before it landed on the path between Mr Cross’s cornfields, roughly where The Pastures is now. All these planes were the old twin wing Tiger Moth models, and came from Denham flying club or White Waltham, and had usually run out of petrol. Eventually another plane came to his rescue, bringing enough fuel to see him home. On another occasion a plane landed in the field at the back of the houses in Littleworth Road, where it meets Coates Lane. Again he was rescued by another plane bringing him fuel. Because planes were so rarely seen in those days anything like this caused great excitement. Another plane which did actually crash, landed on the hill which divides Cookshall Lane from the path leading to Brentwood. We know it as ‘Blue Hill’. The pilot was a Sikh and the only injury he had was a cut across the bridge of his nose. He said that from the air the hill looked like a flat field. When I got to the site the plane was tipped up on its nose with the propeller stuck into the ground. There is another story attached to this though. Bill Bowler was in granddad’s smallholding playing about with the airgun that was kept for shooting rats etc when he heard this plane coming low overhead, and he fired at it just as the engine cut out completely. He was scared to bits thinking that he had it shot down.

Of course the most famous plane to land was that of Colonel Bill Cody which landed in Mannings field in 1912. People came from all over to see this strange machine. I was told that the local farmer tried to charge every one a penny to go into the field, but the excitement was so great that the gates were broken down, and the people flooded in.

I remember being in the playground at the school when Sir Alan Cobham and his ‘Flying Circus’ came over the village, five planes all in different colours, causing great excitement among us youngsters. Apparently he was giving a show from the field where the modern Girls High School now stands and a short flight around the area could be had for 10/- (50p). This was also the field where the annual charter fair came to for a time, and I was taken there for a treat when I suppose I was about nine. It was a fantastic sight, carousels, boxing booths, roundabouts with huge horses to ride on, stalls making all sorts of sweet things, all noise and music from the giant steam driven organs. So much to take in and a truly magical place for a youngster.

At different times, when required, the council would repair the roads. This was another source of excitement to us children. There would be tar lorries spreading lots of hot tar onto the road, being spread over the surface by men in big tar covered boots, using wide brooms. A lorry would follow behind spreading small pebbles all over the surface, and then came the steam roller, which had a massive wheel at the front the same width as the engine. This would travel back and forth, rolling in the stones to make a firm surface. Next day some men would come along with brooms and sweep up all the loose stones- nothing was wasted in those days. I remember when I was really tiny, about three I think, Granddad had just bought me a new Cambridge blue outfit, little shorts and a matching shirt. The first time out in my new outfit, I was on my own for a few moments and thought it would be great fun to sit down on the newly surfaced road and pop the tar bubbles that had appeared in the heat. I was covered in tar all round- legs, socks, new shorts. Poor Gran was really upset because the clothes were ruined, and the money they cost meant that probably something necessary in the house had to be foregone. I’ve felt bad about that ever since I was old enough to appreciate how tough times were for them.

Occasionally a travelling Evangelist preacher would visit the area, going from village to village preaching the good word. In Downley he would erect a large marquee in the field where Burrows house now stands. He had a little harmonium on which he played all the old favourite hymns- ‘The Old Rugged Cross’, ‘Shall We Gather At The River’ etc and we really enjoyed his visits. He wasn’t a tub thumping preacher. Stories from the bible were told in a gentle way and aimed at the enjoyment of the children. On one of his visits to Lacey Green, I think, his marquee was struck by lightening, and I don’t remember him coming around after that. Perhaps he thought he was getting message from above to stop his travels.

Among the other characters that visited the village was the Muffin Man. He carried a large board on his head on which he had muffins and crumpets for sale. These were covered by a black sheet of some kind, and he would advertise his presence by ringing a large brass bell and calling out “Muffins for sale, muffins for sale”. All I can remember about them was that they tasted wonderful and was a special treat. Every year it seemed, an old tramp use to visit the village- ‘Santy’ we used to call him. He had a long beard, a trilby hat and a long coat. He was harmless, and people treated him kindly. I wonder what lay behind his life as a tramp? Wartime experiences, domestic trouble, we will never know. Another regular was the scissor grinder. Somehow he turned a grinding wheel from a connection to his bike, and would sharpen knives scissors, shears etc. I suppose he made a living at it because he called regularly.

One visitor who is always remembered was the Onion Man. ‘Onion Johnny’ we use to call him. He came over from Brittany every year, and would travel around the area selling the onions which hung in long strings on his bicycle. Our regular daily visitor was the Postman, dressed in his smart uniform with his little flowerpot helmet- all the mail in a bag which lay in his red tradesman bike tray. He really did look like a government official.

Well, how did we youngsters spend our spare time. A great deal was spent in the woods, making camps, having a small bonfire and roasting some potato’s which ended up more burnt skin than potato, climbing trees, and occasionally camping out. I remember one summer night a gang of us camped out in a bell tent in the field between Little and Big Tinkers wood. It all went well until about two o’clock in the morning when a herd of cows came over to investigate. They kicked the guy ropes, making the tent move about, that we thought we ought to make a quick get away. So in the middle of the night we were all trying to gather up our blankets, pull down the tent and make a move to the bank below the monument. First we had to get over a barbed wire fence, then try to put up a biggish bell tent on the side of a steep hill not an easy job. In the morning I found that not only had I gashed my leg on the barbed wire but torn the backside of my trousers as well. That escapade dampened my enthusiasm for camping for some considerable time.

We all enjoyed the ‘two penny’ rush to the cinema on Saturday mornings, until I started my job at the farm and grocery store. There was always a cowboy film or a detective film. The stars of that era were Buck Rogers, Gene Autrey, Tom Mix, and their horses, Trigger and Silver, which were almost as famous as them. Dick Tracy and Charlie Chan were the detectives and managed to finish the film each week in terrible trouble so that you just had to go back the next week to see if they had survived.

Quite large groups would meet up and walk down across the footpath known as the Bird in Hand field. It was an enjoyable walk with views across the valley, and at that time skylarks would be singing, and all sorts of birds would be in the fields and hedges. Now they are so rare which is a great loss to everyone.

As we got a bit older several of us had bikes, and would sometimes go for longish rides taking a packet of sandwiches and a bottle of lemonade. I remember several times cycling over to Henley to sit by the river, and one time during the early part of the war riding through Amersham, Chesham, onto Berkhampstead and Aylesbury, where we had a meal in the British Restaurant for 1 shilling and three pence, about 6 pence in today’s money. There was so few cars and lorries in the village that we could play all sorts of street games without fear of danger. There was a game called tiles, which consisted of a stack of small tiles or boot polish tins. The idea was to knock them down and see how many could be replaced before the opposition had collected the ball and hit the tile man with it. At least I think that is what happened. Another game which could be quite dangerous was called ‘cat and stick’. A small piece of wood tapered at each end was placed on the ground, and the idea was to hit one end of this with the stick to make it jump into the air, then to hit it again as far as you could, then run as many times as you could between two set points before the ‘cat’ was returned to the start position. There again I can’t guarantee the accuracy of the way the points are scored but the hitting of the ‘cat’ is correct.

When the daytime schooling and playtime was over we had time to enjoy the indoor pleasures of reading, playing board games like draughts snakes and ladders and a card game called ‘snap’. But perhaps the most interesting pastime was listening to the radio- ‘Dick Barton, Special Agent’ along with his assistants ‘Snowy and Jock’ and left us every night worrying if they would get out of the traps that the evil villains had set for them. The other famous actor on the wireless was ‘Valentine Dyall, The Man In Black’ who broadcast the most frightening stories in a deep voice, really scary , that made you want to look under the bed before you went to sleep. The wireless was so much more entertaining than television- you could create your own mind pictures, and stretch your imagination. Saturday night was always a big night for wireless fans. One interview show was called ‘In Town Tonight’ and would start with the command “Once again we stop the mighty roar of London’s traffic to bring you some of the interesting people who are In Town, Tonight”. This programme was followed by a variety show, which at times included all the old favourites of the day- Jack Warner, Elsie and Doris Walters(?), Tommy Handley and the ITMA gang, Ted Ray, Max Miller, and so many more. All good clean humour and never a dirty word to spoil ones pleasure.

The village hall was a fairly regular place of entertainment. The local Young People’s String Orchestra would play, and I remember Ken Cross the local farmer’s son playing his piano accordion, looking red with shyness in the glare of the spotlight. There was also a local choir which put on a show occasionally, and every so often the Co-op entertainment society would appear and they had all sorts of acts, comedians, singers etc. I suppose by modern standards it seemed amateurish, but we thought it was great fun and made more enjoyable because the performers were all local. Another place of entertainment was the Wesleyan Chapel. Members would put on a show for the youngsters, and I still remember a little ditty from a sketch given by Miss Youens and Miss Stratford(?) both dressed as yokels, complete with smock and wellingtons, “Come Daisy, come Dandelion, come Daffodil, you surely will come to no harm; If you think of the cows in the cowshed, that live down on Mulberry Farm”. I also remember a magic lantern show being given by a retired priest Rev Hinds(?) who lived at the brow of Plomer Hill. He had been a missionary in Africa, and had a wonderful collection of coloured slides to show. We thought it was marvellous to see all these wonderful sights in colour ,and it was a lovely way to spend an evening.

So, our pleasures were simple, but fulfilling. Little did we know what the coming years would bring, but the fear and apprehension was on reflection, continually with the parents of the young people of service age, remembering the terrible toll that the Great War of 1914-18 had taken in the village. Being young we didn’t appreciate all the talk of a coming war that dominated the news of the day. We had heard of Hitler and Mussolini, but did not pay too much attention to it. We had our games to play, pictures to see, even a youth club to go to in the village and in Wycombe as well.

We still played in the woods, and one evening made a fairly big camp ensuring that the boughs covered the top, more like an igloo. This was to make sure that, when we lit a little bonfire in there, any German planes flying over would not see us. What we had not reckoned on was that the boughs were bone dry and by now it was really dark, when all at once a spark must have set fire to part of the hut. In a few seconds there was probably the biggest bonfire that we had ever had. This brought the special police and air raid wardens running down to the scene- at first thinking a plane had crashed, but afterwards promising all sorts of retribution to whoever was responsible. Of course by that time we had dispersed all over the area expressing wonderment at the incident.

By now most of us were eleven and twelve years old, attending the Mill End Secondary Modern School. It seemed massive after our little village school, but I loved my time there, although I think I got the cane off of every master I had, but I still ended up as vice captain of the school- so I could not have been too bad a pupil. The lessons were many and varied: the three Rs, art, geography, history, woodwork and metalwork. Our master for this was also named Bowler. He had a small cane about 12” long, but it used to really sting. He was a wonderful story teller, and one time I had made an iron poker of which I was really proud. However Mr Bowler thought it needed a little more attention to the pointed end, so back into the forge it went. But I was so interested in the tale he was telling that I quite forgot about my poker, and when I remembered about it was too late- it had been in the forge fire too long and had burned right off. Misery for me plus another dose of his little cane, but I can never remember anyone holding grudges for being caned- it almost became a badge of pride. The biggest disgrace was having to go to the Headmaster to have the cane. This was usually for non-class things like being late or scrapping in the playground. One day three of us were sent to him (Mr Green)- Johnnie Green, Jack Chilton and me. Johnnie Green had two strokes from his six foot cane across the backside- Jack Chilton ran out of the room, and Mr Green swiftly shut the door and blocked my escape. So I ended up having six of the best to make up for the others that got away. The other thing he was very annoyed about was that on the walls of the newly built shelter we thought it would be patriotic to write in thick, white chalk V ···- (dot dot dot dash). This was our bit of support for the propaganda war.

Two dates that with hindsight showed that the so called civilized world had gone mad- on September 1st 1939 Germany invaded Poland, and September 3rd Great Britain declared war on Germany. I remember being in the front room that Sunday morning, just me and my Grandma, when Mr Chamberlain made the official announcement. Tears streamed down her face and now I know she was thinking of her sons who would be called on to serve in the forces, and thinking of the terrible toll that the previous war had inflicted on the village.

It was not long before the young men and women were being ‘called up’, a few in the Navy but most into the Army and Air Force. They served in every theatre of the war, and the photographs of the ‘Welcome Home Dinner’ that hang in the village hall show that over a hundred villagers served their country. Sadly there were five men who lost their lives- three members of the Air Force, William Harvey, Kenneth Mullet, and Percy Stratford, Cecil Avery was a soldier, and Roy Carrington was a dispatch rider with the National Fire Service, who tragically was killed in a road accident. They would all have been in their eighties now had they lived, but the phrase that is part of the Remembrance Day service which says ‘They shall not grow old as we that are left behind grow old’ certainly rings true, as I remember them all as bright faced young men just starting out in their chosen professions.

In the early months of the war the great evacuation of children from London began. Our house was very busy at that time because granddad was responsible for placing as many as he could in the village. The women came down with their children from London begging to be taken somewhere, anywhere in fact to escape from the Blitz which was just beginning. We could see the fires raging over the city from several places in the village, and one can only imagine the horror of living in London during that period . There was even a complete school evacuated to Mill End School. This was the Latimer School, and included lots of students and several masters. One took over our class which was the senior one at that time. His name was Mr Carter, a big man with cropped hair and he wore those small glasses called pince-nez and looked just as we imagined a German would look, and we were convinced he was a spy. He also had a habit of picking his nose, causing much sniggering behind the hand from the class. Another teacher was Mr Goodwin who taught music and some other subject which I can’t remember. We also had our first lady teacher at that time. She was only small, but we soon found out she would not stand any nonsense.

The school was formed into four ‘Houses’, and in my last year I was voted Captain of Shelburne. Sport played a big part in our schooldays – cricket, football – but the two big events of the year was the school marathon, and the annual sports day when we had all the races up to 880 yards, the team relay race, hurdles, high jump and long jump. I was never any good at distance running, but managed to win the 100, 220 and 440 yard shorter races. I also won the hurdle race but the general opinion was that I would probably have got round quicker if I had gone underneath the hurdles instead of over the top. In our last year at school Shelburne won the prize for most sporting events, and I was quite proud to receive the trophy from the headmaster.

Well of course the happy days of youth were fading fast, we were all busy finding work. Tanks drove over many of our old routes, and troops and security measures restricted our usual activities. While the period had been very hard for the older generation, still suffering the aftermath of the first Great War and the great depression, for us youngsters it had been a golden time, and the like of which would never be repeated.

This ends part one of my story.